With the recent rumours about Frizell potentially returning to NZ and the persistent questions surrounding the AB blindside position, I thought it would be interesting to take another look at the past, present and future of the 6-jersey.

Specifically, I’m interested in the selection policies and thought processes, why exactly it’s been so hard for the selectors to find a suitable, long-term replacement for Jerome Kaino, and how current candidates in 2025 would fare in the face of historical selection patterns and requirements. In the end, it boils down to the perennial question: what is a blindside, really?

There’s a lot to unpack, as you’d expect. Apologies in advance for the rather lengthy post.

The past: a Kaino-sized hole

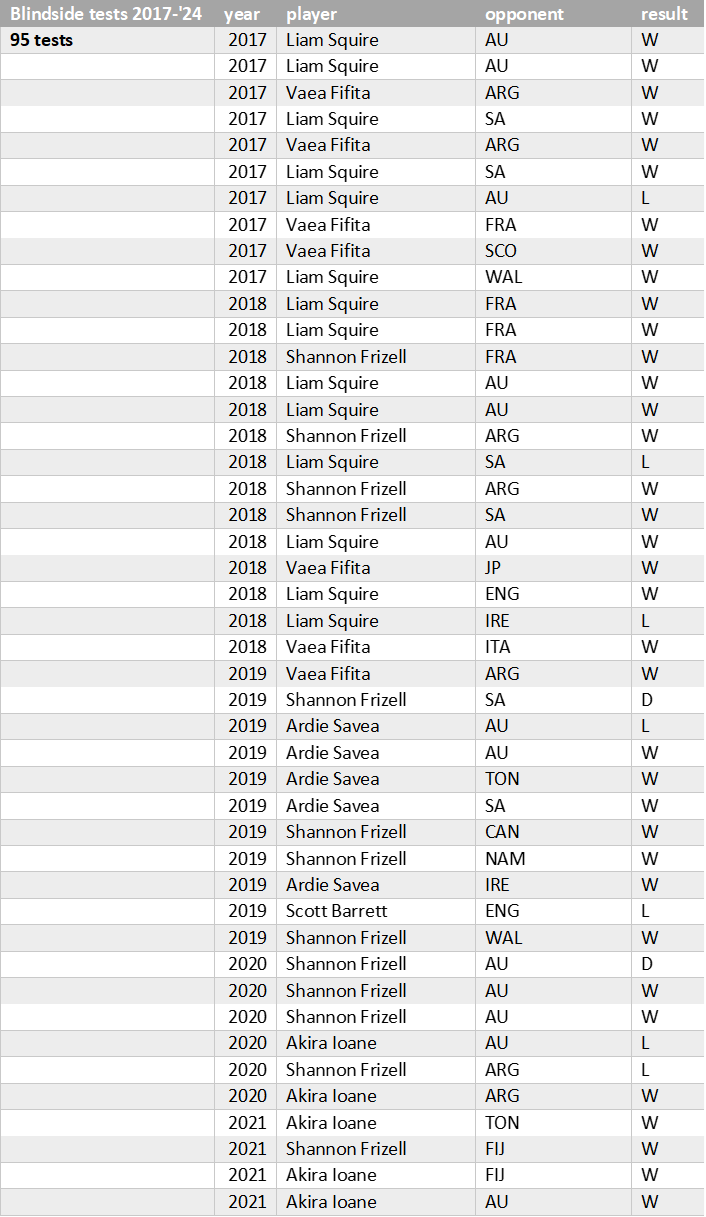

8 July 2017. This was the last Test start for Jerome Kaino in the #6 jersey, against the British and Irish Lions at Eden Park. Since that time, 12 players have worn the jersey across 95 tests over 7 years, with varying degrees of success and duration. This is the list of all the Tests played, the starting 6, opponent, and result.

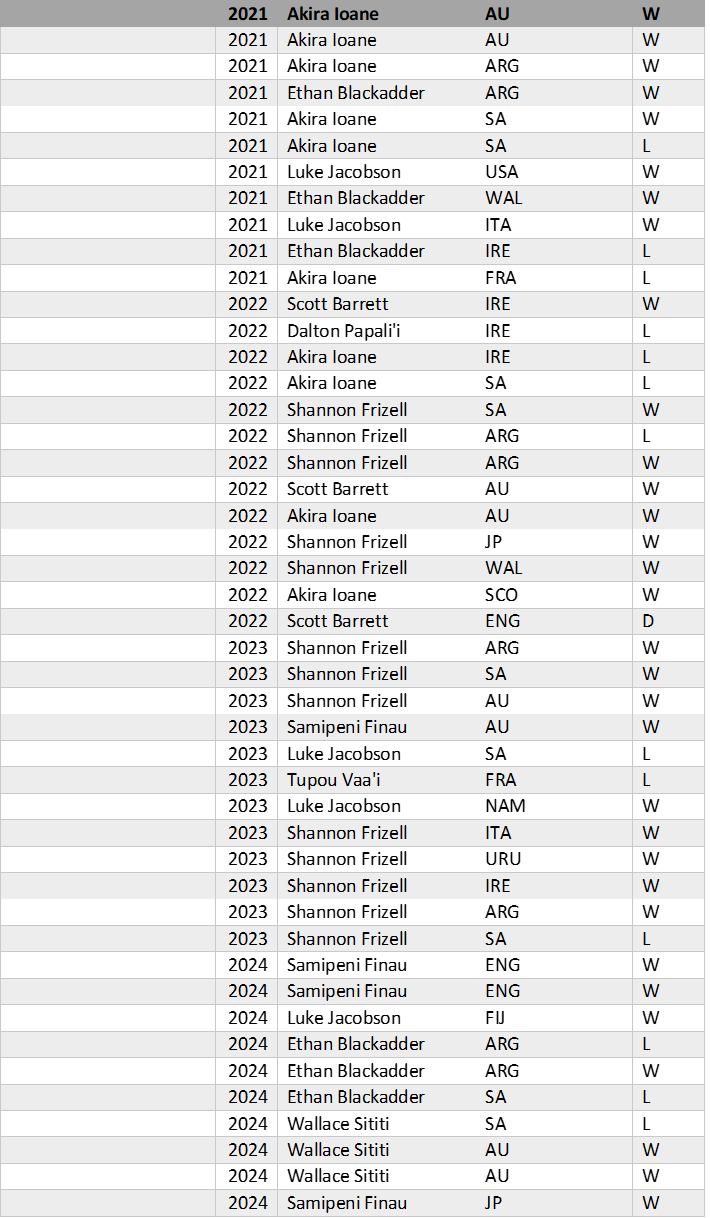

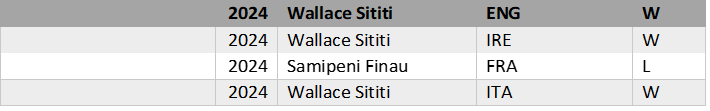

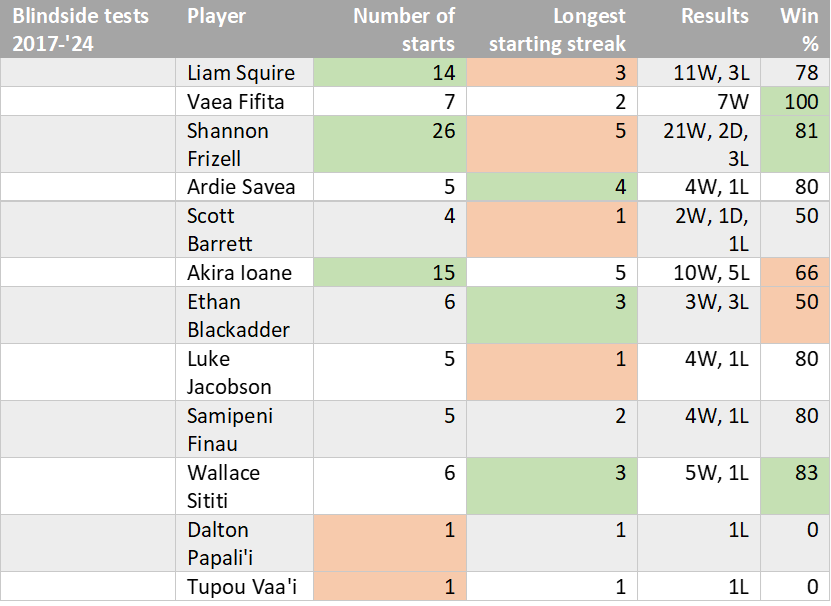

When looking more specifically at some of the cumulative numbers of the different players – number of starts, starting streaks, and win percentages – we get the following table.

I’ve highlighted a few things, Frizell, perhaps unsurprisingly, has been the most consistent name on the team sheet, making 26 starting appearances between 2018 and ’23 as the starting six. Behind him figures Akira Ioane, with 15 starts. Ioane had a somewhat consistent spell in the jersey from 2020 onwards, only to be unceremoniously dumped ahead of the 2023 Test season.

Neither of these two players were ever obvious first-choice selections, with both only ever stringing together 5 consecutive starts. And while rotation is normal – Kaino’s longest starting streak was 9 consecutive Tests across 2 seasons, starting during the 2015 Rugby World Cup and finishing after the 2nd 2016 Test against Wales – both players often lost their place against top tier opposition, something which was much rarer for Kaino from the 2009 season onwards. So the selectors never really settled on a single player, the closest being Frizell during the 2023 Test season, where the selectors seemingly finally backed the Tongan flanker as their main man.

It certainly didn’t help that the post-Kaino heir apparent, Liam Squire, was unable to put together a consistent streak of performances due to a number of factors, only ever starting 3 Tests consecutively as the AB blindside. And while someone like Vaea Fifita had some intriguing performances around this period, the fact that Fifita was the 2nd-choice behind Squire, despite being such a different type of player, already anticipates some of the muddled thinking of then-AB selectors on what they actually wanted from their six.

So what could’ve been some of the factors in this inability to produce consistent blindside appearances? Selection policy is certainly partly to blame: players were put into the jersey without seemingly any sort of preconceived or long-term plan in mind. An example of this is someone like Dalton Papali’i being tested out in the position during a crucial Test against Ireland in Dunedin during the 2022 Test series. When the results don’t go as planned, however, the player isn’t seen in the jersey again. So why was he put there in the first place?

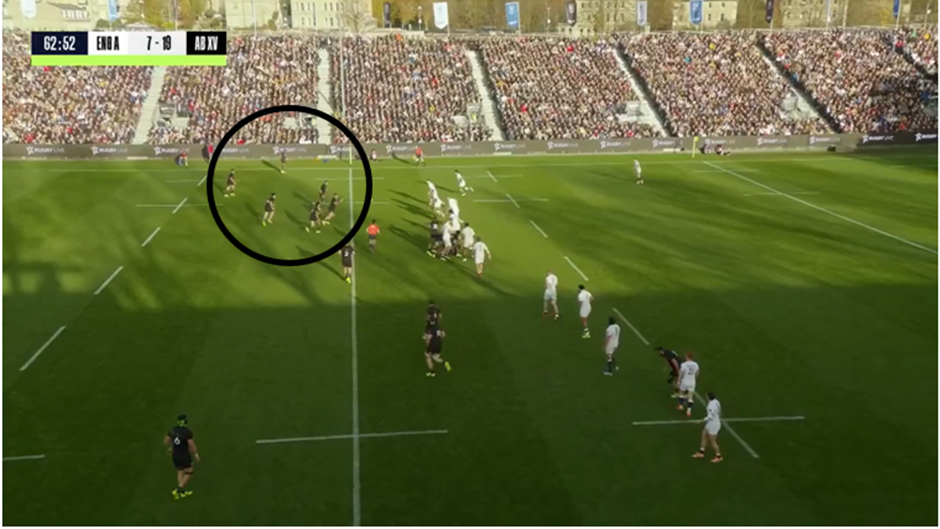

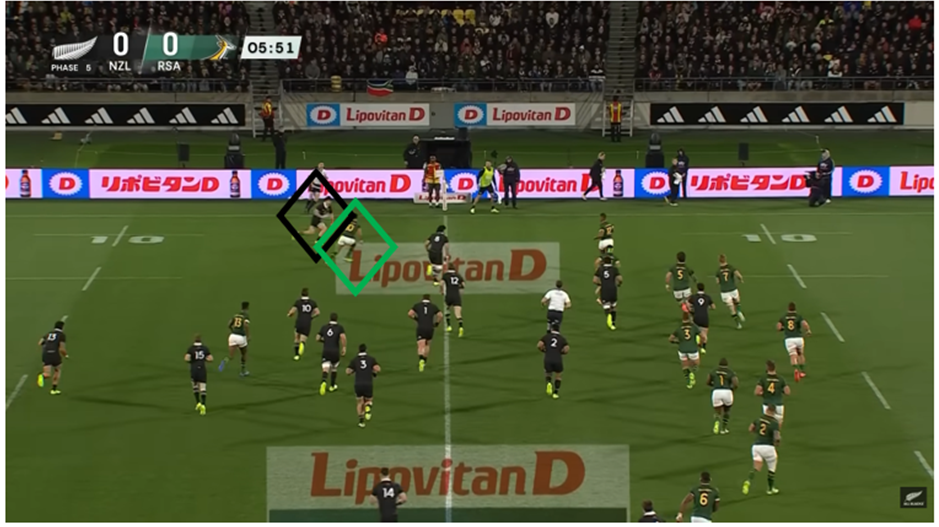

Perhaps the best example of this is the appearances of players in the 6-jersey during crucial World Cup matches who didn’t have any experience of playing there – Barrett against England in the 2019 semi-final, and Vaa’i against France during the 2023 group stages. There seemed to be a too strong belief in the power of tactical surprise and not enough belief in the power of future-proofing from both Hansen and Foster. Faced with obsessive planners during the World Cup – Eddie Jones with England in 2019, Fabien Galthié with France in 2023 – their response seemed to consist solely of the selectorial equivalent of throwing a spanner in the works. Particularly clever, it ain’t.

Why is it so hard for the ABs to find the right six?

Another factor surely is not so much the timing of the selections, but the selected player profiles themselves. The first two blindsides selected after Kaino are a good example of this, Squire and Fifita: one is a hard-nosed flanker who excels in the close quarter collisions; the other is at his best out wide, playing and accelerating into space. Fifita’s own interpretation of the blindside’s role – “I like six, because I can use my athleticism to do what I can do on the outside, rather just stay tight and do the hard work, like running into a brick wall and getting your body tired” – is telling in its own right.

Squire, on the other hand, had a very different view on the requirements of the jersey. Speaking on James Marshall’s What A Lad-podcast, he commented: “I just wanted to run into it as hard as I could... I sort of knew if I could hit someone as hard as I possibly can each time, then I’d most likely win the contact.” It’s hard to imagine more contrasting mindsets as those of Squire and Fifita.

So why were both selected then? My own guess is that the AB selection criteria for the jersey suffer from a kind of schizophrenia, where the selectors really want two playing profiles for the price of one: on the one hand, they want the player to comply to the Test requirements of a proper blindside – someone who is a physical presence, dominates the collisions, while bringing a more dynamic element to core tight five roles such as cleaning and carrying up the middle. This Test blindside has size, grunt and mongrel, which needs to be used to stop mauls, bring carriers down quickly and to smash breakdowns.

This, however, isn’t enough for the voracious demands of the AB selectors, adding on game-specific requirements unique to their own game plans: their blindside needs to do all of the above, while also being comfortable as an edge forward, someone who has an offloading game, attacking vision as well as a genuine athletic edge. It’s not hard to imagine the AB selectors looking at Pieter-Steph Du Toit and telling him to work on his handling and attacking support play.

If this sounds like an unreasonable and overly long list of demands, then you’d be right. To me, one of the foundational reasons for the AB blindside-conundrum is, in other words, self-inflicted, with the requirements of the player simply being too demanding. What is described here are two players, not one. This becomes further obvious if we were to re-classify the previous blindside-suitors into two groups, those of tight and loose blindsides.

It is important to mention now that this distinction isn’t in any shape or form meant to be normative, meaning that one style is by definition better than the other. Both styles are requirements, not options, within the AB game plan. My classification here is mostly based on what I consider to be the respective player’s foremost strength, the style which fits closest to what the player themselves consider to be their bread and butter.

Furthermore, I’m also not claiming that these players aren’t able to thrive playing those other styles. Dalton Papali’i has fantastic abilities on the edge, while Ioane can be destructive in the tight. My argument is more that these players, like almost every other player, excel in a particular part and space of the game, be it in the tight or the loose.

The AB selectors, however, have made no decision on what kind of style they want their blindside to focus on. The six needs to be able to do everything, almost equally well, in their view. This is where the problems start.

The present: decisions, decisions

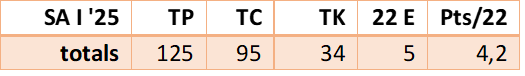

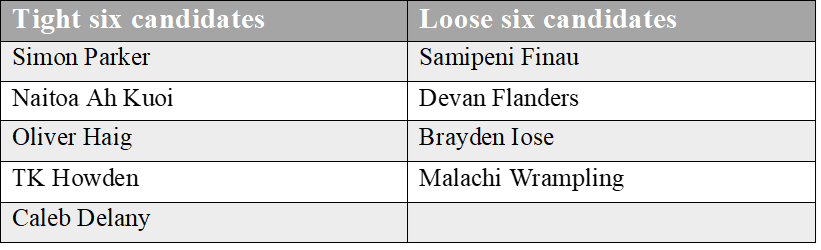

So what does this mean for the present and the upcoming selection of potential AB blindsides? If we were to separate these two styles, as we did above, then the New Zealand rugby landscape offers plenty of potential candidates:

This isn’t meant as an exhaustive table of potential blindside-candidates, more a selection of players who clearly fit one of these two specific playing styles. Others who are more difficult to categorize, like Jacobson, an undersized tight six candidate, I’ve left out for now.

The distinction is pretty clear: the players on the left are typically lock/6s, while the players on the right are equally comfortable at 6 and 8. The players on the left are proficient in the lineout, have high tackle numbers and prefer to spend most of their time in the middle of the field. The players on the right have a more developed attacking identity, able to play in space on the edge, have an offloading game and, importantly, possess rapid acceleration. All of these players can play blindside at Test level. But they are considerably different in their focus, style and areas of specialization.

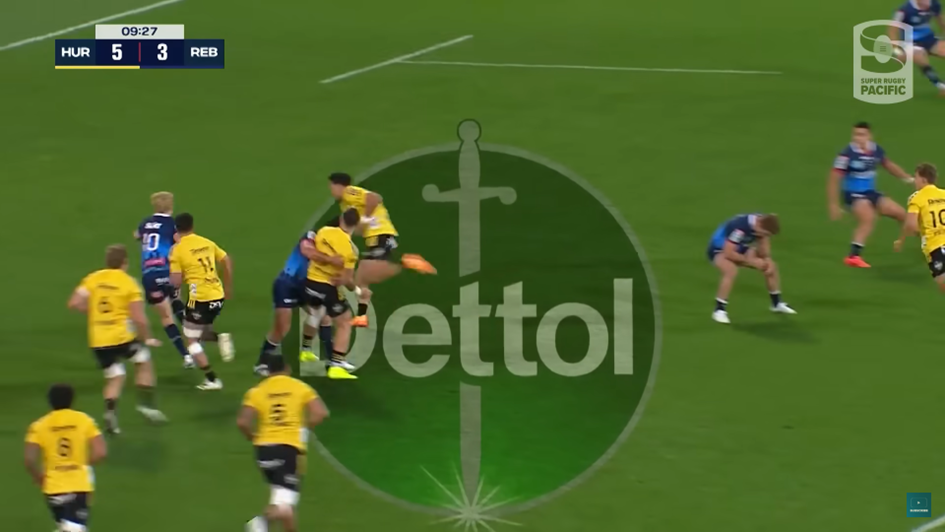

The issues start when tight sixes are being asked to do loose six-roles, and vice versa, something which already acts as a predictor of potential issues at Test level within the AB game plan. Take the Round 10 clash between the Chiefs and the Highlanders, for example, which puts a tight six like Oliver Haig opposite a more loose six like Samipeni Finau. Very quickly, the differences between the two become apparent due to the distinctive nature of each of the two halves.

In the first half, the match was stop-start, a continuous struggle between the two forward packs for territory and possession. The ball went from set-piece to set-piece, from kick to kick, with most of the rugby being played between the 22s as a contest for the ball. This kind of style suits a player like Haig, who likes to play in a supporting role, whether it be in the tackle, carry or clean, alongside the tight forwards.

https://media3.giphy.com/media/v1.Y2lkPTc5MGI3NjExbThva283MngwZGY2dXB5dDh5azI2a2c1eG01ZjExanV2cmVwMWwwaSZlcD12MV9pbnRlcm5hbF9naWZfYnlfaWQmY3Q9Zw/FKYDV7rsQMqIw98wje/giphy.gif

https://media0.giphy.com/media/v1.Y2lkPTc5MGI3NjExYWw3NW83MXR1NmJ6MWw0d2xyM2JiNzZvNzA5MmFwZnhzeHFoc3FkOCZlcD12MV9pbnRlcm5hbF9naWZfYnlfaWQmY3Q9Zw/c1rKRNFGbHElJZ8dHf/giphy.gif

https://media3.giphy.com/media/v1.Y2lkPTc5MGI3NjExNjBiZGN4c3h2MGNtaHpmNWlyMTQ4NGd6d3g1cWxzdWFjNTk5MXdpNCZlcD12MV9pbnRlcm5hbF9naWZfYnlfaWQmY3Q9Zw/4wOzOwCIxzr1ysI0V8/giphy.gif

Playing tight: Haig likes to stay close to his tight forwards, contesting for possession in the middle of the field

Haig could most often be found in or around the ruck in defence, typically in partnership with either Holland or Lasaqa

While Haig seemed to enjoy this contest- and forward-focused first half, a player like Finau thrives in the open spaces with the ball in his hand. When the ball barely reaches the edge, however, due to the nature of the breakdown contest in the middle of the field, Finau finds it more difficult to involve himself in the game.

Finau, away from the ball, calling for the ball to come his way but the movement doesn’t reach the end of the chain

Instead of getting caught up in the forward tussle in the middle of the field, Finau keeps his width, waiting for the ball to eventually come his way. While this width stresses the defence somewhat, it leaves the Chiefs tight five with fewer bodies to contest the breakdown battle.

Again, it’s not as if Finau doesn’t or isn’t able to effectively clean, with this dynamic clean on Renton preventing a certain turnover.

But it’s less of a central facet to his game than it is to Haig: if Brown doesn’t slip, Finau probably continues moving out wide to take up an attacking position rather than execute a dominant clean alongside the Chiefs openside flanker. In contrast to Haig, Finau doesn’t continuously work in pairs, like Jacobson, Brown, Vaa’i and Ah Kuoi do for the Chiefs.

If Haig felt at ease during the first half forward slog, with Finau struggling to get into the game, the roles would completely reverse in the second, with the game suddenly breaking open for the attack.

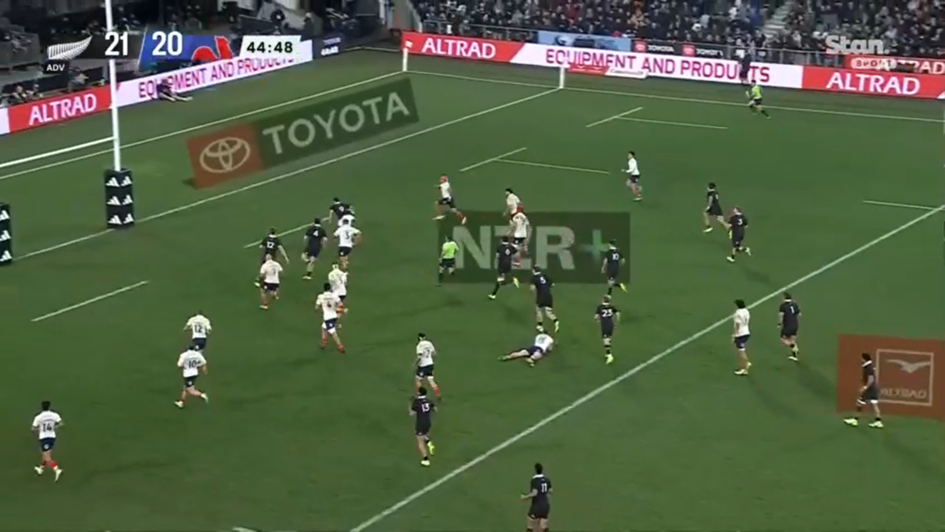

With Finau, you get a player who is incredibly comfortable in open space, who is able to see attacking opportunities unfold before they’ve happened. He also possesses a skillset which is invaluable in unlocking certain attacking movements on the fly. For the Chiefs’ first score after the break, Finau first runs a great, self-spotted line from the lineout, while then calling himself as the spontaneous backdoor passer in the following phase, when the ball shifts back to the open.

https://media1.giphy.com/media/v1.Y2lkPTc5MGI3NjExcm9kY2lzZjFyMW1ndncyOHEzYnl2bm0xNTd0ZDU1dnJkZ3c3N2k5ciZlcD12MV9pbnRlcm5hbF9naWZfYnlfaWQmY3Q9Zw/gwrmYDxdPbpEWhMDQR/giphy.gif

https://media0.giphy.com/media/v1.Y2lkPTc5MGI3NjExZGhqMnJscm5qa29vd3p3MHZoa3RjMGpjM2lzdDR3Mm81cndnN25oaSZlcD12MV9pbnRlcm5hbF9naWZfYnlfaWQmY3Q9Zw/sodTK6xzOqjGF4RSZ3/giphy.gif

Here, Finau is at his best, acting as a crucial link player between forwards and backs. Ten minutes later, Finau’s persistence on the edge would be rewarded when McKenzie finds him with a well-executed cross-kick.

The contrast in attacking sensibilities between Haig and Finau is strong. While the latter is like a fish in water in attacking spaces, the former looks more like a deer in headlights. In a rare moment when the ball came to him in attack on the edges, Haig struggled to move away from his natural tendency to play a supporting role and keep his width.

Early in the first half, for example, with the ball moving out wide with the Highlanders on attack, Haig needed to drift on his opposite, creating space for his inside man while providing the latter with a legitimate passing target. Instead, Haig’s tight instincts immediately kick in, looking to position himself on his inside man’s shoulder as a support and cleaning option.

But the unintended effect is that the space becomes shut down as well as the attack, with the Highlanders being saved from being turned over courtesy of an earlier penalty advantage.

During the second half, with the game breaking up a bit more, Finau started to thrive while Haig struggled to find his feet out wide, the latter being hooked relatively quickly in the half with TK Howden coming on.

Both Finau and Haig’s issue, in other words, is that they struggle to switch up how they play, making them relatively dependent on the in-game context for them to be effective rather than being able to impact the game no matter the type of contest. And this is where the blindside’s role becomes important. As the player who connects the tight five with the loose forwards, the blindside is a player who needs to be able to take on a multitude of roles and styles: sometimes playing creatively on the attacking edge, and sometimes playing in close support, being closely bound with the tight forwards in collective play.

More than anything, it’s what the ABs seemingly demand from the position, as someone who can play in the right style, at the right time. This is, however, far easier said than done, and Finau’s and Haig’s contrasting skillsets show why. While both have their own unique strengths, playing as the AB 6, they will be expected to be equally proficient in both the loose and the tight.

But when this isn’t a skillset which comes particularly naturally to those players, they are on a hiding to nothing. We have seen how players, when faced with the difficult demands of Test rugby and Test coaches, start playing outside of their natural game. It’s easy to imagine how both players would look to overcompensate their own perceived weaknesses in the Test arena – Finau starting to play tighter and more conservative, Haig looking to force himself to stay wide on attack – to detrimental effect.

Someone like Taniela Tupou is on record as saying how he’s starting to feel like he doesn’t know how to play rugby anymore, after constantly being told to change certain parts of his game. A similar difficulty potentially awaits AB blindsides, as long as the selectors have such ambitious demands of their number six.

Future: the key(s) to the blindside position

So what is a blindside, really? From an AB perspective, more than a lineout option, a physical presence, an edge forward, or a collision specialist, the ideal blindside is essentially someone who is equally proficient in tight and loose responsibilities. And, perhaps even more importantly, is someone who has mastered the art of knowing when to play tight and when to play loose, at the right time.

Wallace Sititi did an admirable job during the 2024 Test season as an interim blindside: his incessant work rate and energy allowed him to be (relatively) effective in both tight and loose situations, showing up all over the field while being a bruising physical presence. But Sititi is about as natural a number 8 as there is: he will carry relentlessly and put his team on the front foot, using both his considerable physical power as well as his skillset to break tackles and gain terrain. He seems destined to end up at the back of the AB scrum.

So what are the options available to the coaches? What the AB selectors will be looking out for, I think, is a player who falls into one of the two aforementioned categories, but who shows genuine ability in playing the other style as well. And the player who has shown the most improvement in this sense, during the 2025 SR season, has been Simon Parker. Parker has always been a player of promise, a big body who moves well and shows solid technique in the tackle, carry and clean. But what he has shown this season is a new dimension on attack, a willingness to play a central role on attack.

This moment late in the recent game against Moana Pasifika highlights Parker’s newfound confidence on attack, first throwing the wide pass before running the support line and throwing a beautiful offload for the Ratima try:

https://media3.giphy.com/media/v1.Y2lkPTc5MGI3NjExaWJranNyN3dhNGY0ZHczNjlkaXZ3cGEybjJrYzlweGl6Z3hzMzlkdyZlcD12MV9pbnRlcm5hbF9naWZfYnlfaWQmY3Q9Zw/l6So3PzPz4KvnFQXkz/giphy.gif

Parker double involvement on attack

To look at this development a bit more closely, the game against the Crusaders in Round 2 nicely encapsulates the growth of the Kaiwaka flanker’s game. In the first half, Parker was able to display his traditional strength, his work and physicality in the tight exchanges.

https://media4.giphy.com/media/v1.Y2lkPTc5MGI3NjExNWtvenkyMmV1emJibzRmdXJ6bnE2NzA1YmRqdnEzZG8zNnJ0cnJwdiZlcD12MV9pbnRlcm5hbF9naWZfYnlfaWQmY3Q9Zw/9IoYbe6a56gyXjKe7r/giphy.gif

https://media3.giphy.com/media/v1.Y2lkPTc5MGI3NjExanZpbW4xOXg5czUxd3E0Yjd3ajN4MGNmNzR0d2lncjl4eWxvbTI5biZlcD12MV9pbnRlcm5hbF9naWZfYnlfaWQmY3Q9Zw/MPllaDkgOTiapPArHF/giphy.gif

https://media0.giphy.com/media/v1.Y2lkPTc5MGI3NjExOHE1NzNuYTFiYjhnNTg3a2p2NGZvejY0ZWIwM2E4b3UyYmFzbnA4ZSZlcD12MV9pbnRlcm5hbF9naWZfYnlfaWQmY3Q9Zw/AfOSsVXff4wfjJm2zL/giphy.gif

https://media2.giphy.com/media/v1.Y2lkPTc5MGI3NjExZ2V5YzZ6N2FhdHIyODFmaTZhdWd0dG54c3JsOHNsNWE1ZnVsb3Y5MSZlcD12MV9pbnRlcm5hbF9naWZfYnlfaWQmY3Q9Zw/JTmzEB7ApGAHCBrEpR/giphy.gif

https://media1.giphy.com/media/v1.Y2lkPTc5MGI3NjExeHR3ZWcyaHM3Y2Vqc3k4NjhkNm95aHoycDZpaWtqdnQ2amN3aGp5NiZlcD12MV9pbnRlcm5hbF9naWZfYnlfaWQmY3Q9Zw/hpy11LYrbmhDK3guuH/giphy.gif

Aggressive cleans, dominant tackles, multiple involvements on both attack and defence through the middle, typically in close cooperation with the tight five

But what he has improved upon this season is his development of a genuine attacking game, running great lines, being creative in the wider channels and showing a deft array of passing.

https://media0.giphy.com/media/v1.Y2lkPTc5MGI3NjExMjlmZ29ycDJtd20wNm05eDN1Z3hucWoxazE4NXQxOHNyZ3Rucjc2eCZlcD12MV9pbnRlcm5hbF9naWZfYnlfaWQmY3Q9Zw/I1a04C1COzUoPS4jCX/giphy.gif

https://media1.giphy.com/media/v1.Y2lkPTc5MGI3NjExMHVpd3FsM2Z1Y3psc3ZlaXpvMnF2ZnI2ZGw1MGN4NWZ4ejh2YWk5biZlcD12MV9pbnRlcm5hbF9naWZfYnlfaWQmY3Q9Zw/QNwdF4d1UrPxJuT8FE/giphy.gif

https://media4.giphy.com/media/v1.Y2lkPTc5MGI3NjExOGlwOXNzcGtuNHl6ZHlkMGZkbGtobTR5dDNhdzIyajIwcTd3dmlybCZlcD12MV9pbnRlcm5hbF9naWZfYnlfaWQmY3Q9Zw/PoXmnESTDElVgMwmnb/giphy.gif

https://media3.giphy.com/media/v1.Y2lkPTc5MGI3NjExNjhocGhvZng0c21rNHYydDR0b2V5OTJkNzR5YnFuN2ZsNjh1OGRkbCZlcD12MV9pbnRlcm5hbF9naWZfYnlfaWQmY3Q9Zw/yLXWJ3AS3gGblagnSc/giphy.gif

Number 8 skills from Parker: finding gaps and keeping the attack alive

So someone like Parker will be of great interest to the AB selectors, as he fits the template of an AB blindside, currently. He is able to impact the game, no matter the type of encounter, due to his ability to be efficient in both the tight and the loose. The grunt of a lock and the soft skills of a number 8, this is, in the end, what they are looking for in a blindside flanker.

For a final note on this already way too long collection of thoughts, it’s relevant to emphasize the importance of coaching in Parker’s development. The Chiefs have been clear about how they want to play during games, taking on the opposition pack in a direct tussle during the first half in order to tire them out, before playing a more expansive game in the second. Parker clearly knows his assignments during each half, making it easier to balance between tight and loose styles of play and to make decisions on attack and defence.

Herein also lies a key directive for the AB coaches in their search for a new blindside: clarity around game plan and requirements eases the task of the blindside flanker, who already has to juggle different styles and roles across 80 minutes on the field. There are plenty of suitable candidates in NZ to be a quality number 6 at Test level: what is needed is a clear selection policy as well as a straightforward plan, which allows these varied skillsets to shine. Whether it be a tight or a loose blindside, or someone who is able to switch between the two, performance starts with the long-term planning and vision of the AB coaches. And looking at the state of the jersey for the past 7 years, it’s clear they have some work to do.