Will the NZ U20s finally have a stable scrum platform in 2026?

A recurring question with the NZ U20s is whether they will have the set piece platform to compete with the big packs of South Africa, France and England. It’s a question that fascinates me, which is why I watched a lot of scrums from NZ U20 eligible props these past few weeks, to get some insight into the matter. After reviewing the footage, my personal verdict was that they could get a stable scrum platform but getting selection right as well as healthy props would be critical. There is not a lot of depth right now and there are some structural issues within the NZ rugby pyramid blocking the creation of further depth.

The data

So how did I try to gain this insight into the propping stocks? The short answer: by watching a ton of scrums. I watched a minimum of 15 scrums per prop, looking at a total of 23 NZ U20 eligible loose- and tightheads. My goal was to get an impression of two things: are they able to scrum within the limits of the laws, and are they able to exert any sort of dominance? In other words, I exclusively considered their ability in the scrum; whether they can tackle, carry or clean isn’t taken into account here.

I tried to keep my selection of props as broad as possible: players who were selected for NZ U18 rep teams, provincial U19 teams as well as SR U20 teams, all of those came into the frame. There were only 2 real limitations for players to come into consideration: they needed to be born on January 1st 2006 or later (which wasn’t always easy to figure out). And second, there needed to be available footage of them scrummaging. Due to this condition, players like Apai Ma’u Hinkes (North Harbour) and John-Paul Schmidt (Auckland) weren’t included, despite their promise and potential, as I simply couldn’t find enough film of them scrummaging.

When watching these scrums, I mainly noted whether the props were penalized and whether or not the scrum was moving forward. Since scrums are notoriously difficult to fully comprehend, I did not try to distinguish between who was actually at fault. For example: if Dane Johnston was at tighthead and part of a scrum that folded but the ref indicated that it was the loosehead who collapsed, I still counted the penalty against Johnston. While this isn’t particularly fair, it allows me to simply measure whether props are part of successful scrums, as a kind of external measuring point. In order to combat any false perceptions, I made sure to watch scrums from different match settings for a single player, where he scrummed with different teammates. This should’ve balanced the overall picture.

Scrums are as much about perception as anything else; I was more interested in these perceptions as well as the referee’s interpretations of these pictures as a way of gauging the NZ U20 propping stocks. Gathering this information (was the scrum penalized? Did the scrum move forward?) eventually resulted in this table, a total of 830 non-unique scrums that included 23 NZ U20 eligible props.

Listed here are the props, the number of their scrums I watched (S), their scrum penalties won (SPW), conceded (SPC), free kicks won (SFW), free kicks conceded (SFC) and how often their scrum moved forward (SMF)

Based on both the viewing of these scrums as well as the results they brought forward, I was able to formulate two predominant findings: (1) there is a dominance issue within NZ rugby, and (2) representative selection strategies do not sufficiently prioritize set piece excellence.

Finding 1: the dominance issue

The easiest way to build a successful scrum is to find a tighthead who is not only able to keep up the scrum but who is also able to move his pack forward as well. While these forward movements might not always be fully legal, they present the picture of a dominant scrum, which most referees find difficult to ignore.

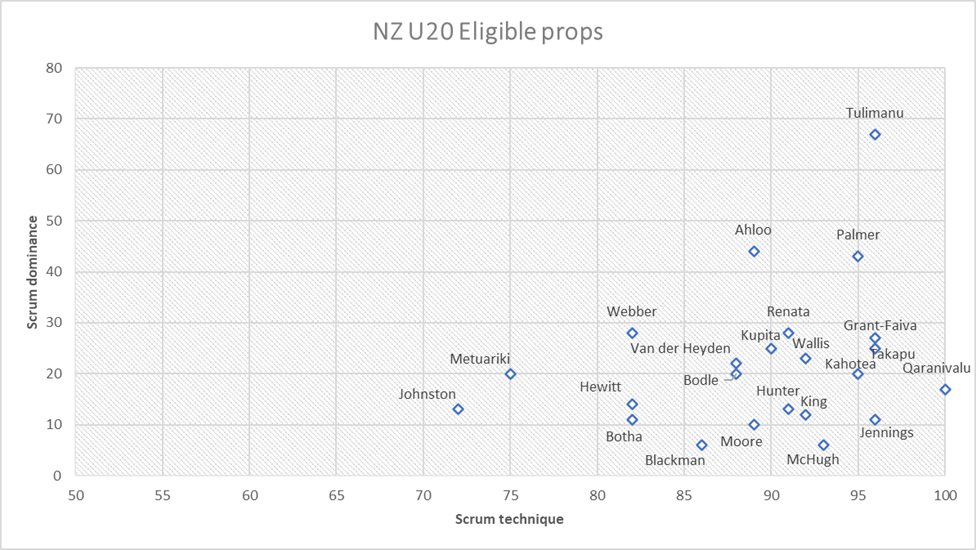

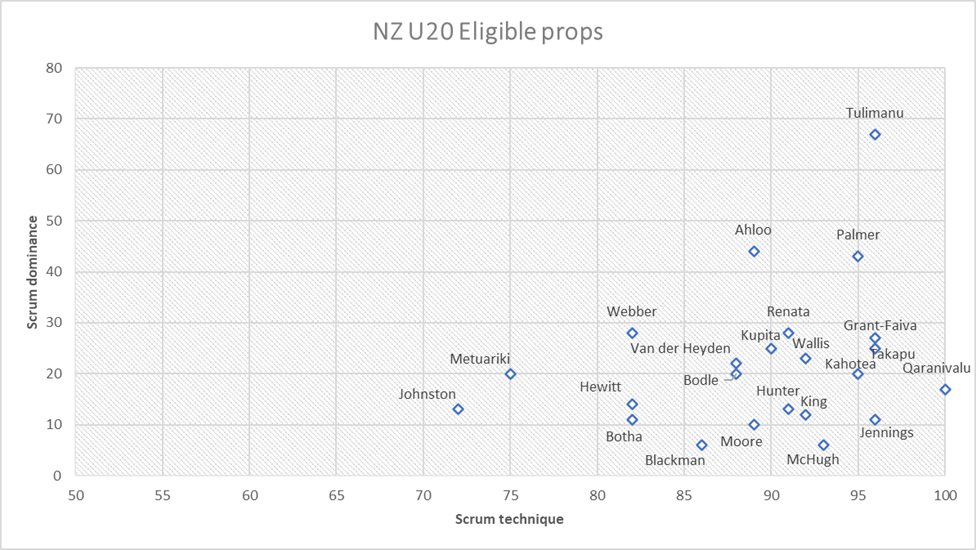

And yet, remarkably few props within NZ age grade rugby seem interested in such forward momentum, preferring instead to take a conservative approach of keeping the scrum up and letting their opposites make a mistake. The following graph, based on the data from the table above, further emphasizes this trend.

Westlake man-mountain, Kaiva Tulimanu, is the exception that proves the rule, with most props preferring to prioritize scrum technique over scrum dominance

Kaiva Tulimanu has been a dominant force in age grade rugby, not just in his bullish carries but in his scrummaging as well, moving forward in his scrums at an excellent rate of 67%. And yet his exceptionality is damning: while Ahloo and Palmer still show decent aggression in their scrummaging (at 44 and 43% respectively), nobody else cracks even the 30%. They prefer to simply keep the scrum up (‘scrum technique = percentage of scrums completed without conceding a penalty or free kick’) and make sure the ball gets away safely.

The refereeing of the scrum, especially by NZ referees, plays a considerable part in this. Watching all of these scrums throughout different age grade competitions – First XV, U18 rep games, U19 provincial competitions, and the SR U20 tournament – it becomes obvious that NZ referees (1) are more or less fine with messy scrums, and (2) are very hesitant to reward scrums for their dominance. If the ball is in any way playable, refs will want to keep the game moving.

One of the clearest examples that I encountered of this, was in the 3rd/4th playoff at the National Top 4 tournament this year, between Westlake Boys’ and Southland Boys’. Throughout the game, Tulimanu put his opposite, Presley McHugh, pretty much through the wringer, moving forward at will, both on his own and on opposite feeds.

Tulimanu vs. SBHS I

Tulimanu vs. SBHS II

Tulimanu vs. SBHS III

Rarere, the SBHS 9, is feeding the scrum nearly at the feet of the number 8 in order to get the ball away, yet wasn’t penalized once for this. Nor was the collapse in the final example

The game was played in windy and wet conditions, where territory was absolutely crucial. Yet, Westlake didn’t get any benefit from their set piece dominance, not being awarded a single penalty from the scrum throughout the game, despite being completely on top in this area. As a result, Southland didn’t suffer any territorial disadvantages and were able to win the game, 21 to 19.

It is at this point that the structural issue causing the lack of dominance becomes more apparent. Kiwi refs very rarely penalize any other indiscretion at the scrum apart from the collapse. Hookers popping out of the scrum, tightheads boring in, looseheads losing their binds, brake foots not being placed properly: a NZ ref will tend to ignore these things, if the ball is playable. This was further underlined when Tulimanu would once again face off against McHugh, this time in the game between the NZ Barbarians U18 and Māori U18, with the same result: dominance for little reward.

Tulimanu vs. McHugh v2

The Māori U18 scrum isn’t able to take the hit yet the ball is still deemed to be ‘playable’

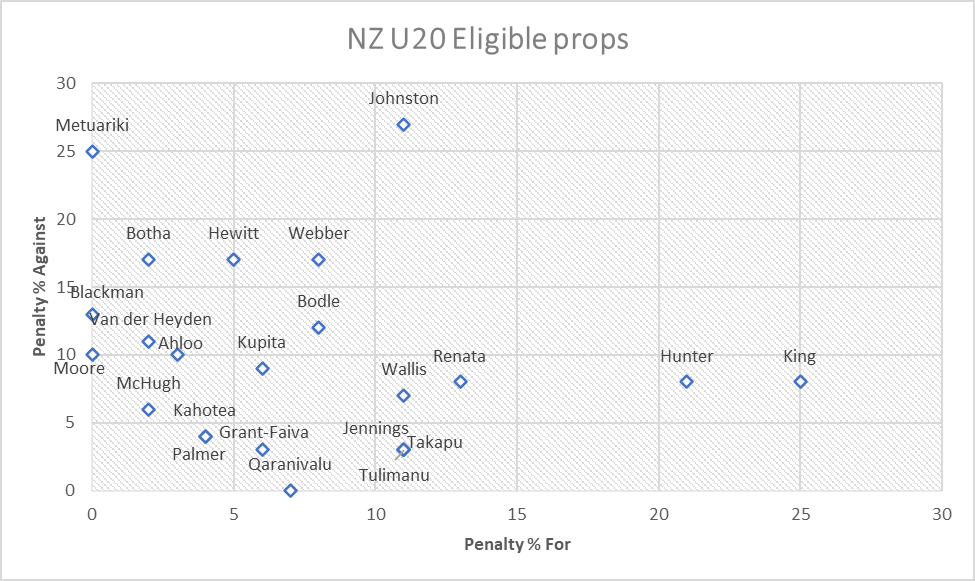

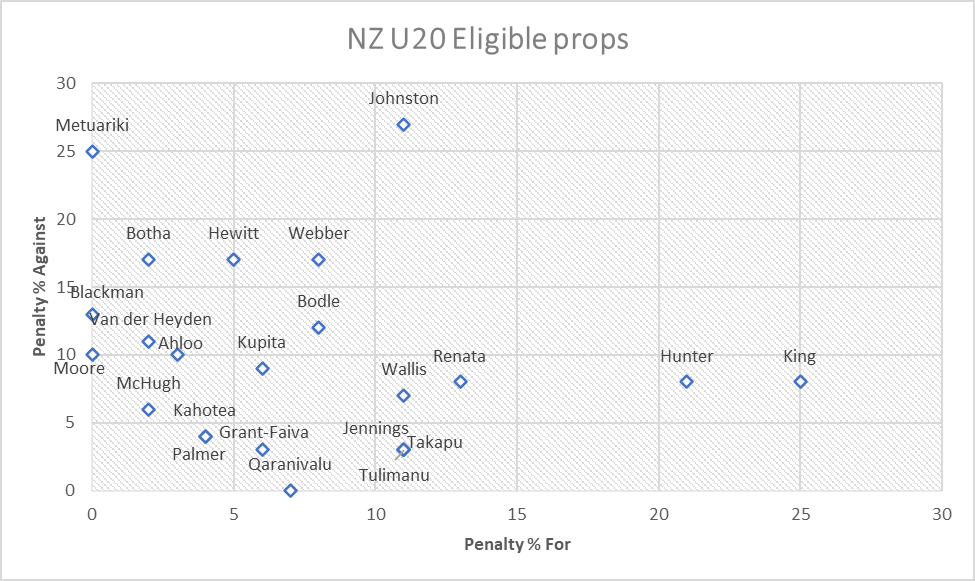

This also explains why two of the least ‘dominant’ scrummagers, Corban King (12% dominance) and Henry Hunter (13% dominance), were rewarded the most at scrum time: their opposites were deemed to collapse the scrum.

Not moving forward but still being rewarded: Hunter and King reaped the rewards of their set piece conservatism

While there is no fundamental problem with simply keeping up the scrum as a set piece tactic and prioritizing playable ball, there are, however, several contingent problems this creates. One of those already mentioned is the lack of incentive for set piece dominance. A player like Tulimanu isn’t sufficiently rewarded for his scrummaging dominance so why would First XV coaches emphasize a set piece that is coherent and moving forward if it doesn’t deliver anything in the long run? As long as the scrum sort of holds up, no matter how ugly, chances are you won’t be punished for this.

The downside of this lack of incentive is that NZ rugby isn’t producing enough polished props who want to be dominant in the scrum. A second yet related problem is the difference in how the scrum is policed at World Rugby-level: in contrast to NZ refs, non-Kiwi refs are much more strict on the finer details of the scrum. As a result, simply producing playable ball is no longer deemed enough: the scrum needs to be able to take the hit and present a stable scrum before the ball is deemed playable.

For example, in the game against Georgia at the U20 World Championships in Italy, the NZ U20 scrum struggled, not just because of the strength of the Georgian scrum but equally because of the technical rigour and eager whistle of the Italian ref, Filippo Russo.

NZ U20 scrum vs. Georgia I

NZ U20 scrum vs. Georgia II

First, the ball has already left the Georgian scrum (and is, thus, obviously playable) yet the ref still awards them a penalty for dominance. And in the second, Johnston is penalized for binding early for a second time, a very technical offence that simply doesn’t get penalized in NZ age grade rugby

NZ props aren’t sufficiently prepared for this kind of technical rigidity by their own refs, who simply let too much slide and who aren’t willing to sufficiently reward scrum dominance. Equally, it immediately brings us to a second finding, which is the inability of NZ Rugby to take this refereeing discrepancy into account with their selection strategies.

Finding 2: failed selection strategies at the national level

There is substantial evidence that NZ selectors – both for NZ Schools at U18 level and for NZ U20s – simply do not place enough value on the worth of a dominant scrum. The key term seems to be, once again, ‘playable’: it is deemed sufficient if the scrum can hold up on its own feed and deliver playable ball to the backline, especially if it means the possible selection of mobile props. Sika Pole, Robson Faleafa, Dane Johnston, Logan Wallace, Bradley Crichton, Ben Ake, Gabe Robinson (just to mention a few) are all props selected for the U20s in the last few years who had obvious difficulties in the scrum but were still selected for the team, due to their ball-in-hand abilities.

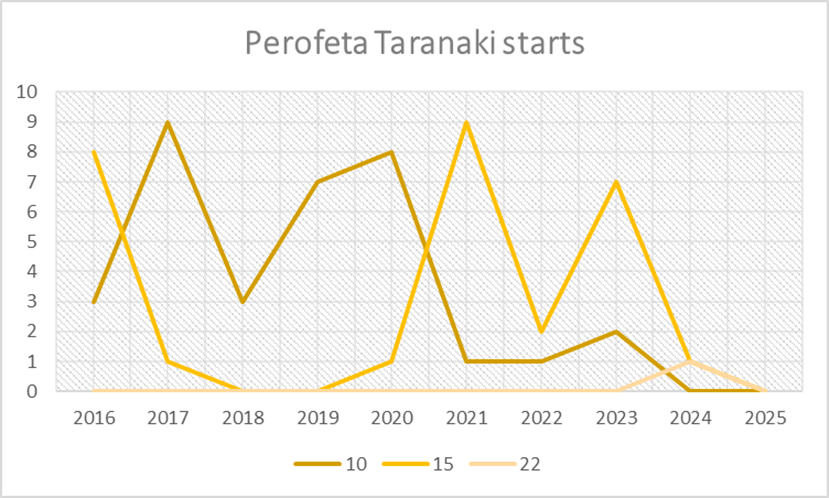

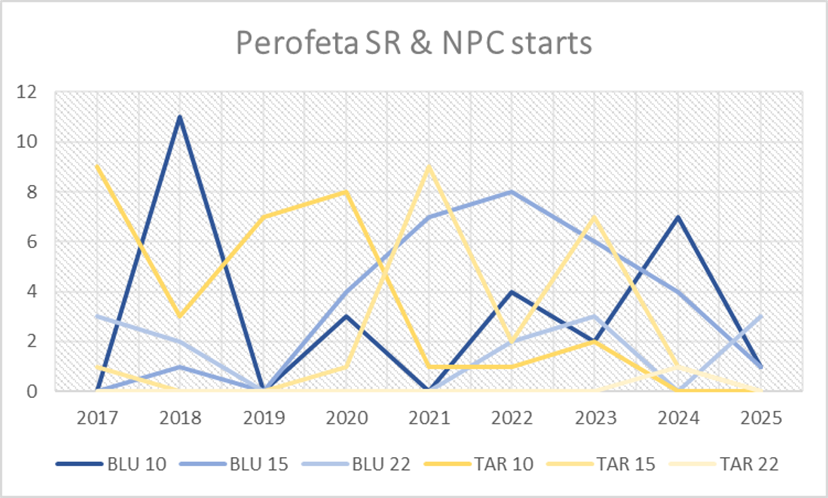

Johnston is probably the most glaring example in recent years. Regularly penalized at all levels – whether playing for Feilding (First XV), NZ Barbarians U18, or Chiefs U20 – Johnston was still selected as an under-ager for the NZ U20s this year, with rather predictable results. The Taranaki prop typically struggles to properly balance his weight after the bind, often leading to the collapse.

Johnston scrum for Chiefs U20

Johnston losing his feet after the engage

Despite this tendency, Johnston was still selected for the NZ U20s and played each game at the U20 World Championships. While he was regularly penalized at tighthead (3 penalties across 4 games), it was when he was used as a loosehead in the opening pool game against Italy that things really went south. In a close and tense affair, Johnston put in a 20 minute-cameo where he was penalized three times for collapsing the scrum, giving Italy opportunity after opportunity to get back into the game.

Johnston vs. Italy U20 I

Johnston vs. Italy U20 II

Johnston vs. Italy U20 III

Being in the unfamiliar loosehead position, Johnston is unable to control his weight after the hit

While Johnston isn’t a particularly reliable tighthead, the NZ selectors decided to further compound their set piece insecurity by putting him in an unfamiliar loosehead position. This, what can only be termed as a lack of respect for scrum specialists, is a theme which returns again and again in national selection strategies.

Changing from tighthead to loosehead (or vice versa) can turn a strong scrummager into a set piece liability. Two other examples of this ill-advised selection strategy are Tamiano Ahloo (Auckland, Blues) for the NZ U20s and Cody Renata (Waikato, Chiefs) for NZ Schools: both are strong tighthead scrummagers who were put in an unfamiliar loosehead position, with poor results.

Their set piece strength at tighthead, however, was easily apparent. Ahloo, for example, put in a strong showing for NZ Barbarians U18 against the highly-fancied Kingsley Uys from Australia U18s, while Cody Renata was consistently dominant alongside a hefty Rotorua forward pack all the way through to their National Top 4 title.

Ahloo at tighthead vs. Australia U18 I

Ahloo at tighthead vs. Australia U18 II

Renata at tighthead vs. Feilding I

Renata at tighthead vs. Feilding II

Stability and strong go-forward momentum: while scrum dominance might not always be fully legal (with Renata seemingly angling in), it creates a positive picture in the referee’s mind

Both Ahloo and Renata were undoubtedly selected with these performances in mind. When picked for their national rep sides, however, they were put at loosehead. Plenty of props have already commented how difficult it is to switch between the two positions, with Angus Ta’avao’s particular metaphor being perhaps the most memorable – “It's a whole different side of your body. Imagine going to the toilet and being right-handed, then you've got to use your left hand, so it's like little things like that” (Ta’avao, 2019).

Both Ahloo’s and Renata’s performances further proved Ta’avao’s point: Ahloo and Renata both struggled to keep their balance in the scrum, their body dynamics clearly not used to the hit on the other side of the scrum.

Ahloo at loosehead vs. Australia U20 I

Ahloo at loosehead vs. Australia U20 II

Renata at loosehead vs. NZ Barbarians U18 I

Renata at loosehead vs. NZ Barbarians U18 II

The selection policy falls flat: both Ahloo and Renata are unable to hold up their unfamiliar side of the scrum

These selection strategies aren’t without consequences, either. In both games – NZ U20s vs. the Junior Wallabies at the 2025 U20 TRC, and NZ Schools vs. NZ Barbarians U18s – these faltering set piece platforms set the stage for opposition comebacks, with the NZ Barbarians just falling short whereas the Junior Wallabies were able to salvage a draw after being behind by 12 points and being down to just 13 men at a certain point.

It points to a high-performance unit at NZR which is both being impeded by the system it put in place as well as its own selection strategies, which refuse to take into account the reality of World Rugby’s more strict refereeing framework for the set piece.

There’s a saying often attributed to South Africa’s Danie Craven, the legendary coach and administrator, about how the first person selected should be the tighthead and the second the reserve tighthead. The new ‘Doc’, Rassie Erasmus, has shown no hesitation to listen to and borrow from Kiwi rugby culture in areas such as counter-attack, leading to success at both senior (TRC) and junior level (U20 World Championship). It’s about time NZR listens to some wisdom from the Republic and put more emphasis on set piece dominance.

As far as selection is concerned, the options seem relatively straightforward to me: it’s Kaiva Tulimanu and Tamiano Ahloo as your two premier tightheads.

Summary, or tl;dr

Can the NZ U20s have a stable platform in 2026? I believe so but only on the condition that the NZ selectors get it right and select for dominance. There is not a lot of propping depth in NZ rugby right now, mostly due to playing philosophy, refereeing standards and selection issues. But the cream still rises to the top, and a few props can put in a good showing, I believe, if selected and put in their natural position.